What Are the Metrics Tracked on a State Government Spending Analysis Dashboard?

State governments manage complex budgets, dozens of programs, and thousands of transactions each fiscal year. A well-designed spending analysis dashboard turns this complexity into a set of actionable metrics that help lawmakers, budget officers, auditors, and the public understand where money is going, how efficiently it’s being used, and whether policy goals are being met.

Below are the core metrics typically tracked on a state government spending dashboard, what each metric means, and the practical levers leaders and analysts can use to influence them.

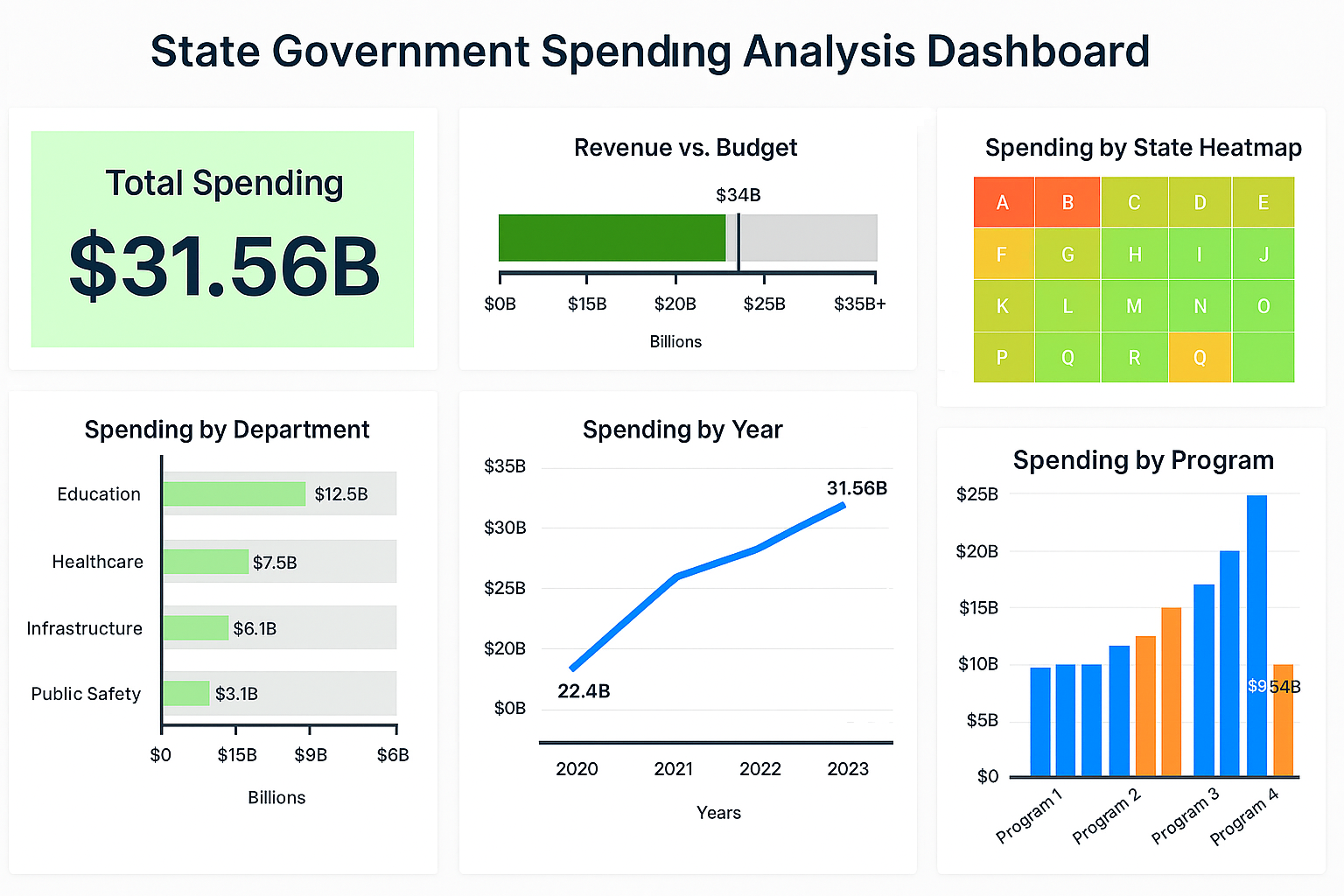

Total Expenditures (Actual vs Budget)

What it means: The total dollars spent by the state during a period, shown alongside budgeted amounts and prior-year comparatives. This is the fundamental measure of fiscal activity, often broken down by department, program, fund, and object class.

How to affect it: Control total spending through mid-year budget reviews, targeted reallocations, and hiring or procurement freezes. Improve forecasting accuracy to set realistic budgets, and implement tighter encumbrance controls so planned spending is visible before it becomes a cash outflow.

Budget Variance by Agency / Program

What it means: The difference between budgeted and actual spending, usually expressed in dollars and percentage. Positive variance can mean underspending; negative variance indicates overruns.

How to affect it: Tighten budget execution with real-time monitoring and monthly variance reporting. For chronic overruns, investigate root causes (underestimated demand, contract escalations, or operational inefficiency) and correct budget assumptions during the next cycle. Implement pre-approval workflows for large commitments to reduce surprise spending.

Expenditure Growth Rate

What it means: Year-over-year percentage change in spending overall or within categories (personnel, capital, grants). This metric signals trend direction—whether spending is accelerating or being contained.

How to affect it: Use policy levers (hiring freezes, cap on non-essential travel, renegotiation of vendor contracts) to slow growth. For structural growth (pensions, healthcare), focus on long-term reforms or phased adjustments rather than one-off cuts to avoid service disruptions.

Program Cost per Outcome / Unit Cost

What it means: The cost associated with achieving a unit of outcome (e.g., cost per student served, cost per mile of road maintained, cost per child in foster care). It links spending to programmatic outcomes and is central to value-for-money analysis.

How to affect it: Improve efficiency through process redesign, bulk procurement, shared services, and technology automation. Benchmark similar programs (in other states or against private-sector providers) to find efficiency gaps. Where unit costs are high because of poor outcomes, redesign the program to focus on results rather than inputs.

Administrative Overhead Ratio

What it means: Percentage of total spending consumed by administrative costs (management, IT, HR) relative to program delivery. It provides a quick view of how much of the budget goes to support versus direct services.

How to affect it: Consolidate back-office functions across agencies, pursue shared procurement and IT platforms, and push routine tasks to digital channels. However, be cautious: excessively low overhead can starve necessary capacity for oversight and program management.

Capital vs Operating Spend

What it means: The split between one-time capital expenditures (infrastructure, buildings, major equipment) and recurring operating costs. This helps assess long-term investment versus ongoing maintenance of services.

How to affect it: Rebalance investment timing to smooth peaks in capital spending, prioritize projects using objective scoring (benefit-cost), and consider alternative financing (public-private partnerships) for large projects. Beware shifting operating costs into capital (or vice versa) merely to meet short-term fiscal targets.

Encumbrances and Outstanding Commitments

What it means: Funds that are legally committed (purchase orders, contracts) but not yet spent. Tracking encumbrances prevents double-counting and gives a clearer picture of available budget authority.

How to affect it: Enforce timely close-out of purchase orders and require periodic reconciliation of open commitments. Implement automated alerts for stale encumbrances and require justification before renewing long-standing commitments.

Vendor Spend Concentration

What it means: Share of total procurement dollars going to the top vendors. High concentration can indicate dependence on a small set of suppliers or potential procurement risks.

How to affect it: Diversify supplier base through competitive bidding, encourage participation from small/local businesses, and break large contracts into smaller, modular procurements where feasible. For unavoidable concentration (specialized services), negotiate stronger SLAs or consider multi-year contracts with performance clauses.

Grants and Subventions Tracking (Disbursement vs Drawdown)

What it means: For funds sent to local governments, nonprofits, or institutions, this metric tracks allocated amounts versus actual drawdowns and outcomes. It reveals whether grantees are using funds efficiently and meeting milestones.

How to affect it: Improve grant management with milestone-based disbursements, better reporting requirements, and technical assistance to grantees. Use dashboard alerts to identify slow spenders or underperforming grantees and intervene early.

Cash Position and Liquidity Metrics

What it means: Short-term cash balance, projected cash inflows/outflows, and days of operating liquidity available. States need to monitor liquidity closely to manage payroll, debt service, and emergency expenditures.

How to affect it: Improve cash forecasting, time the receipt of revenues (tax collections, federal reimbursements) strategically, and manage short-term borrowing prudently. Use delayed disbursement windows when appropriate, and maintain a prudent reserve or rainy-day fund policy.

Debt Service and Leverage Ratios

What it means: Debt service as a percentage of revenues, debt per capita, and other leverage indicators. These measure the sustainability of borrowing and fiscal flexibility.

How to affect it: Limit new debt issuance to high-return capital projects, lengthen maturities to smooth annual debt service costs, and aim for strong bond-rating metrics (e.g., reserve levels, diversified revenue base). Where feasible, pursue refinancing to lower cost of debt.

Fraud, Waste, and Error Indicators

What it means: Flags from audits, anomalous transaction patterns, duplicate payments, or irregular vendor invoices. These metrics quantify potential leakage from the system.

How to affect it: Strengthen internal controls, implement automated anomaly detection, require segregation of duties, and maintain a whistleblower/reporting mechanism. Prioritize audit findings and measure remediation rates as a KPI.

Program Outcome and Impact Metrics

What it means: Outcome measures (e.g., employment rates after workforce programs, graduation rates for education spending, road condition indices for transport projects) that link dollars to real-world results.

How to affect it: Shift toward performance-based budgeting where feasible, require clear outcome metrics in program design, and fund rigorous evaluation. Use pilot programs and randomized trials to identify what interventions deliver the best return on investment before scaling.

Equity and Distributional Metrics

What it means: Measures that show how spending and services are distributed across geographies, income groups, or demographic categories—critical for assessing fairness and compliance with policy goals.

How to affect it: Reallocate program resources to underserved areas, implement targeted grants, and adopt equity impact assessments during budget planning. Track whether reallocation improves access and outcomes for prioritized groups.

Administrative Processing Metrics (Time-to-Pay, Time-to-Approve)

What it means: Operational KPIs showing how long it takes to process invoices, approve contracts, or disburse grants. These affect vendor relations and program effectiveness.

How to affect it: Streamline approval workflows, digitize forms and signatures, set service-level targets, and use performance dashboards for procurement and finance teams. Reducing processing times can also reduce late-payment penalties and improve vendor participation.

Putting Metrics to Work: dashboards that drive decisions

Metrics are only valuable when they are visible in the right context and tied to clear actions. A good state spending dashboard groups indicators into domains—financial health, program performance, procurement risk, and operations—and provides drill-down paths from summary KPIs to transaction-level detail. Alerts and thresholds (e.g., budget variance > 5%, vendor concentration > 20% for a single supplier) turn passive reporting into prompts for intervention.

Finally, maintain transparency and public access where appropriate. Public-facing slices of the dashboard increase accountability, build trust, and often surface useful stakeholder input that improves program design. Internally, couple dashboards with a governance rhythm—monthly budget reviews, quarterly performance hearings, and annual audits—so insights become policy actions rather than ignored numbers.